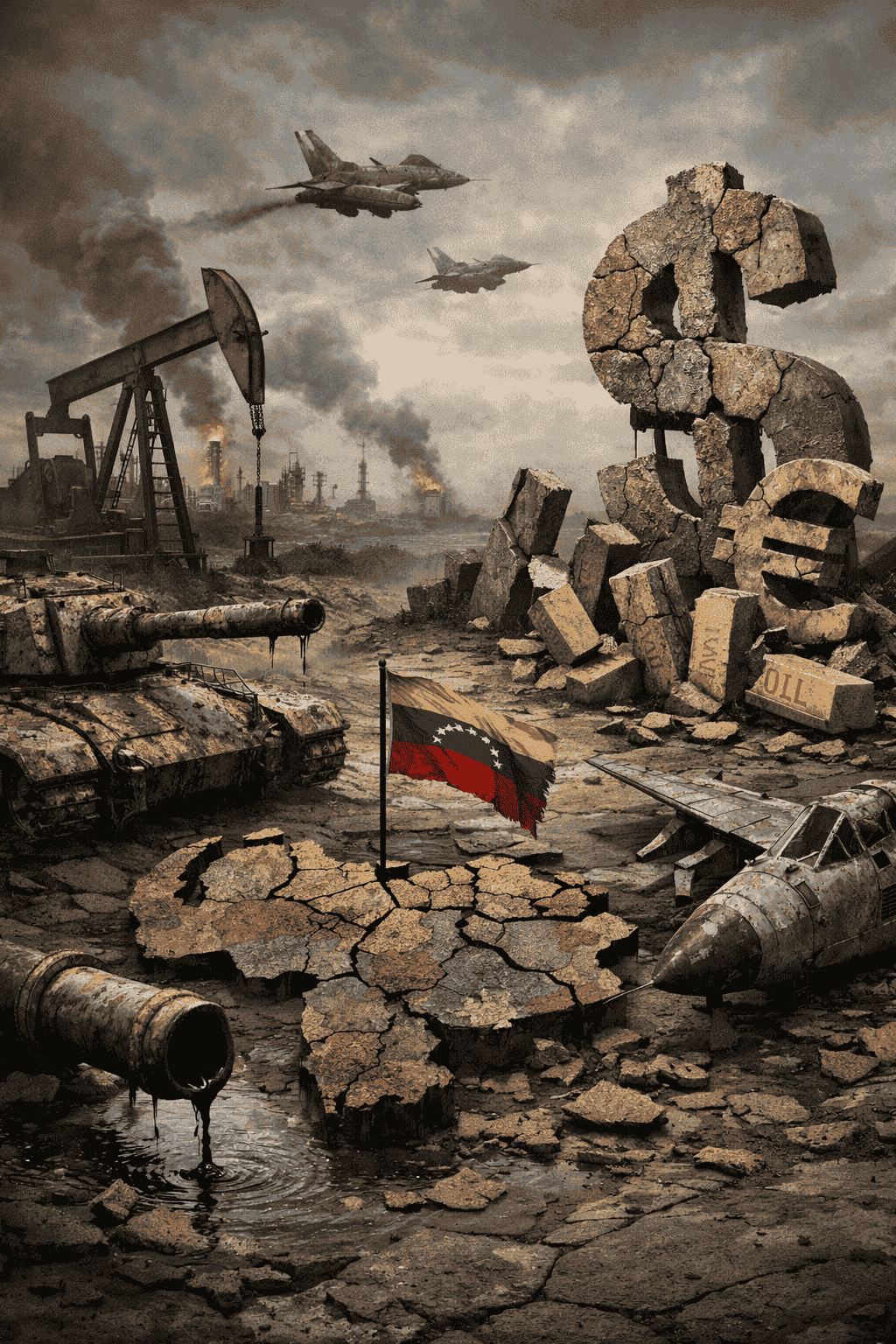

Petrodollars and Military Readiness: How Financial Power Shapes Defence Capability - The Venezuela Case

Military power is commonly evaluated through visible indicators: force size, weapons inventories, or headline defence budgets. These measures, however, often obscure a more decisive variable, financial access. In modern defence systems, readiness is sustained not by possession of platforms alone, but by continuous integration into global financial and logistical networks. Currency liquidity, payment channels, and access to foreign exchange determine whether forces can train, maintain equipment, and remain operational.

Venezuela offers a stark illustration of how the erosion of financial power translates directly into military decline. Over the past decade, the collapse of petrodollar revenues and restricted access to dollar-based financial systems progressively hollowed out the country’s armed forces. This degradation did not occur through battlefield defeat or formal disarmament. It unfolded through sustainment failure, doctrinal contraction, and strategic dependency, demonstrating how financial pressure can function as an indirect yet effective instrument of defence containment.

Petrodollars as an Enabler of Military Readiness

Modern militaries are sustained through cash flow rather than capital stock. Combat aircraft, naval vessels, and air defence systems require uninterrupted funding for spare parts, software updates, fuel standards, and specialized maintenance contracts. These inputs are typically priced in foreign currency and embedded within transnational supply chains that operate predominantly in dollars.

For oil-exporting states, petrodollars historically provided the liquidity necessary to participate in this system. Dollar-denominated oil revenues enabled predictable defence spending, long-term procurement planning, and integration into global sustainment networks. Military readiness, in this sense, was not merely a function of national budgets but of currency compatibility with the defence ecosystem.

Venezuela’s armed forces were built on this foundation. As long as oil revenues could be converted into usable foreign exchange, defence capability remained viable even in the absence of cutting-edge technology or expeditionary ambition.

From Resource Backing to Financial Fragility

At its production peak around 2010, Venezuela produced approximately 3.1 million barrels of oil per day, generating the foreign exchange that underwrote both state spending and military operations. Oil income enabled defence expenditure exceeding USD 5–6 billion annually, sufficient to sustain conventional forces, operate combat aircraft, maintain naval assets, and conduct regular training cycles.

This financial base deteriorated sharply over the following decade. By 2023–24, oil output had declined to roughly 950,000–1,000,000 barrels per day, representing a contraction of nearly 70 percent from peak levels. Export revenues fell even more dramatically. Whereas the oil sector once generated tens of billions of dollars annually, total oil export earnings were estimated at around USD 4 billion in 2023.

Despite this collapse in absolute income, oil continued to account for approximately 58 percent of state revenue in 2024, underscoring the paradox at the heart of Venezuela’s defence predicament: structural dependence persisted even as the resource base shrank. The result was not diversification, but fiscal compression.

Defence Budgets Without Operational Meaning

The decline in petrodollar inflows translated directly into defence spending contraction. Venezuela’s military expenditure fell from multi-billion-dollar levels in the early 2010s to an estimated USD 3–4 million in 2023, according to international datasets. At this scale, defence budgets cease to function as operational instruments.

To put this figure in perspective, sustaining a single modern combat aircraft squadron, including maintenance, spare parts, and training hours requires expenditures far exceeding Venezuela’s total annual defence outlay. Naval readiness cycles and air defence system maintenance impose similarly high foreign-currency costs. A defence budget measured in single-digit millions cannot support even minimal readiness across combined arms forces.

This divergence between force structure and funding produced a military that existed administratively but not operationally. Equipment inventories remained nominally intact, personnel remained on payrolls, and institutional hierarchies persisted. Yet the capacity to translate these inputs into usable combat power steadily eroded.

Sustainment Failure and the Hollowing of Capability

The most acute effects of financial isolation were felt in sustainment rather than procurement. Modern military platforms degrade not through age alone, but through deferred maintenance and reduced usage cycles. Restricted access to dollar-based transactions, particularly following the expansion of financial sanctions from 2017 onward, disrupted Venezuela’s ability to procure spare parts, contract foreign maintenance services, and sustain logistics chains.

Aircraft availability declined as flight hours were curtailed to preserve aging fleets. Naval vessels faced postponed refits and reduced operational tempo. Training exercises were scaled back due to fuel constraints and limited logistics support. Over time, these incremental compromises compounded into systemic readiness failure.

Importantly, this process produced what defence economists describe as a “hollow force”: a military that retains platforms and personnel but lacks the sustainment capacity to deploy them credibly. Venezuela continued to field combat aircraft, air defence systems, armoured vehicles, and a force of roughly 100,000 active personnel, supplemented by a large auxiliary militia. Yet the gap between inventory and usability widened steadily.

Doctrinal Contraction Under Financial Constraint

As conventional readiness declined, military doctrine adjusted to financial reality. Venezuela’s armed forces increasingly shifted away from external deterrence toward internal security and regime preservation. This was not simply a political choice; it was a structurally induced adaptation.

Conventional manoeuvre warfare is resource-intensive. It requires sustained training, high equipment availability, and reliable logistics. Internal security operations, territorial defence, and militia-based structures impose far lower financial demands. Faced with shrinking resources and restricted financial access, the military recalibrated toward missions it could still afford to execute.

This doctrinal contraction illustrates a critical defence insight: military strategy follows sustainment capacity. When the financial foundations of conventional power erode, armed forces prioritize control over deterrence and survival over projection.

Currency Constraints and Strategic Dependency

Loss of petrodollar access also reshaped Venezuela’s defence relationships. Defence procurement is inseparable from currency access. Restricted participation in dollar-based markets narrowed the pool of viable suppliers and complicated long-term modernization planning. Procurement increasingly relied on politically aligned partners willing to transact through credit arrangements, barter, or alternative payment mechanisms.

While these arrangements provided limited relief, they introduced new forms of dependency. Credit-based acquisitions reduced fiscal flexibility; fragmented supply chains complicated sustainment; and interoperability with global defence systems declined. Over time, the cost of maintaining existing platforms increased even as readiness fell.

This dynamic highlights a broader strategic reality: currency access structures alliance options. Financial isolation does not merely constrain procurement; it reshapes security alignment and increases long-term dependence on a narrower set of partners.

Financial Power as Defence Containment

The Venezuelan case demonstrates how financial instruments can achieve outcomes traditionally associated with military containment. By restricting access to petrodollar revenues and global financial systems, external pressure reduced Venezuela’s military readiness, constrained modernization pathways, and weakened deterrence credibility, without direct military confrontation.

This form of pressure operates below the threshold of armed conflict, making it strategically attractive. It avoids escalation while producing cumulative defence effects that are difficult to reverse. From a security perspective, this represents an expansion of the battlespace: financial systems have become an operational domain through which military power is shaped.

Conclusion

Venezuela’s experience illustrates how military capability erodes not through sudden collapse, but through sustained financial deprivation. The loss of petrodollar access did not dismantle the armed forces outright. Instead, it hollowed them from within—undermining sustainment, distorting doctrine, and reshaping strategic alignment.

For defence planners and security analysts, the lesson is clear. In a global system where military readiness depends on integration into financial and logistical networks, currency access is a core enabler of defence power. Control over financial flows can weaken armed forces as effectively as traditional military pressure, redefining how power is exercised in contemporary geopolitics.

References

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). SIPRI Military Expenditure Database: Venezuela.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Country Analysis Brief: Venezuela.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Oil Market Reports (various years).

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). World Economic Outlook Database.

- Macrotrends. Venezuela Military Spending.

- Al Jazeera. Venezuela Explained in Maps and Charts.

- CEIC Data. Venezuela Crude Oil Production and Export Statistics.

- Reuters. Coverage on Venezuela’s Oil Sector, Sanctions, and Armed Forces (various reports).

- United States Department of the Treasury. Sanctions Programs and Restrictions on PDVSA.

- Brzoska, M. (2018). “Economic Sanctions and Military Capabilities.” Defence and Peace Economics, 29(3), 299–318.

- Farrell, H., & Newman, A. (2019). “Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion.” International Security, 44(1), 42–79.

- Smith, R. (2014). Military Economics: The Interaction of Power and Money. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ross, M. (2012). The Oil Curse: How Petroleum Wealth Shapes the Development of Nations. Princeton University Press.

- Drezner, D. W. (2011). Sanctions Sometimes Smart: Targeted Sanctions in Theory and Practice. International Studies Review, 13(1), 96–108.

- Cordesman, A. H. (2019). Sanctions and Security: The Strategic Use of Economic Pressure. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).